The covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of public health at a new level for decision makers. Heavy demands have placed additional pressure on the health workforce and uncovered major gaps and emerging issues such as health equity (CIHR, 2021). A recently updated framework for health care improvement, the quintuple aim, offers a way forward (Itchhaporia, 2021). This framework involves improvement planning for: 1. improved patient experience, 2. using evidence to strive for better health outcomes, 3. strategies to lower healthcare costs, 4. aiming to support clinician well-being and 5. addressing health equity (see figure 1). The relevance and application of a value-based framework has been gaining traction internationally in recent years, especially in Canada, as leaders desire a transformation to healthcare systems (Kokko, 2022). This transformation will lead to better health and an improved economy. As a health professional in provincial public health evaluation and planning, this is a reflection on the quintuple aim and what each strategic aim offers toward influencing the health of Canadians within the healthcare system in Alberta and Canada.

Figure 1.

Evolution to the Quintuple Aim Framework (Itchhaporia, 2021).

1. Improved Patient Experience

Patient experience refers to the kind of interactions an individual has in the healthcare system. In public health, patients access healthcare services not only in hospitals, but in all settings (home, schools, community, workplaces, health centers etc.) and for a variety of health issues (communicable diseases, injury prevention, immunizations, disease screening, health promotion, safe environments etc.). Patients access these services in an effort to prevent and treat illness and disease but also to maintain health and wellness. To provide patient-centered care healthcare teams must respect patients' preferences, values and definitions of health (Tzelepis et al., 2015). The definition of health has evolved, as many individuals today are thriving with multiple chronic conditions and lifespans are longer than ever before (Fallon et al., 2019). According to van Druten et al. (2022), when considering the definition of health, a health care provider may have a different perspective than the patient themselves, which may be different yet from that of policy makers. This makes it difficult for the health care system to meet the needs of a patient, when differing views exist. Improving patient experience in health care is not as simple as having access to services, but rather meeting the complex needs of patients as unique and autonomous individuals. For example, the Public Health Agency of Canada reports on rates of COVID-19 immunizations across Canada, despite universal access to this important health service, the average is 83.1% (2022). Furthermore, see figure 2, regional differences are seen, with rates of 95.7% in Newfoundland and Labrador, or as low as 79.6 % in Northwest Territories. This demonstrates that in addition to personal preferences and beliefs, political and social forces also influence the health of patients.

Figure 2.

Vaccination Coverage by Canadian Province (PHAC, 2022)

2. Better Outcomes

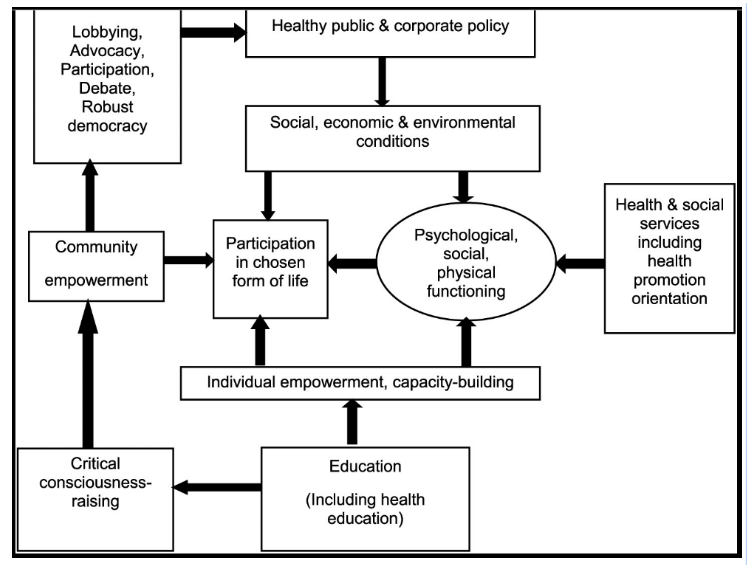

Health outcomes refers to changes in an individual or population well-being because of specific interventions (CIHI, n.d.). The social-ecological model is a useful guide in planning comprehensive strategies for action at multiple levels to produce better health outcomes (Wold et al., 2018). For public health efforts to be effective, for example, at screening programs for cancer, we cannot just look at strategies to influence individual behaviors. Simply targeting an individual's awareness of a screening tool for colorectal cancer will not be effective at early diagnosis and prevention of poor treatment outcomes for late-stage cancer. A whole community approach based on the social-ecological model (see figure 3) includes healthy public policy, strategies to create supportive environments for all health issues (psychological, social or physical) along with building capacity and empowering individuals to build healthy personal skills to achieve better outcomes (Wold et al., 2018). In this example, multi-level strategies could be awareness campaigns for communities, system strategies like sharing of data on electronic records among health practitioners and policy changes to which patients are eligible for screening (Kim et al., 2020).

Figure 3.

Whole Community Approach to Health Promotion (Wold et al., 2018).

3. Lower Costs

Chronic disease rates are on the rise and costing the healthcare system more than ever. According to a report by Fraser Institute, Canada has the highest cost of healthcare compared to similar systems, but it is not performing in terms of the value of its medical resources or clinical performance (Moir & Barua, 2022). For example, in Ontario, a recent report by Canadian Cancer Ontario and Public Health Ontario (2019) show that chronic diseases cause approximately ¾ of deaths in Ontario and cost $10.5 billion annually (CCO and PHO, 2019). The most common chronic diseases that cause death are cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic lower respiratory diseases and diabetes, see figure 4. There are known preventable risk factors including tobacco use, physical inactivity, inadequate vegetable and fruit consumption and alcohol consumption that directly contribute to these chronic disease rates (CCO and PHO, 2019). Across Canada, public health spending (including health promotion of these risk factors) is on average only 5.6% of total health expenditure (CIHI, 2018).

Figure 4.

Causes of Death in Ontario in 2015: All Causes and Chronic Disease Causes (CCO and PHO, 2019).

Regional comparisons can add depth to understanding more about contributing factors to healthcare costs. In Alberta, according to the Report of the Auditor General (2014) medical care of patients with chronic diseases accounts for nearly ⅔ of hospital stays, ⅓ of all visits to physicians and more than ¼ emergency visits. The distribution of health care costs across patients in Alberta can be correlated to the management of their chronic disease. Patients with late stage and poorly controlled chronic diseases account for nearly ¾ of all direct patient costs, while healthy patients living with chronic diseases account for only 2% (Auditor General of Alberta, 2014).

This demonstrates the need to enhance funding for health promotion efforts to prevent chronic diseases by targeting nutrition, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol reduction) as well as increasing multidisciplinary collaboration resources to support effective management of chronic diseases (AHS, n.d.). Collaboration opportunities for chronic disease management also present as cost saving and quality improvement strategies. In Alberta, chronic disease management coordination is separated across not only Alberta Health Services, Alberta Health, Primary Care Networks, Family Physicians, Physician Specialists and Pharmacists (Auditor General of Alberta, 2014). An emerging issue is the need to differentiate and optimize between public health services and primary health care to enhance the effectiveness of our system for chronic disease prevention and management, (Kryzanowski et al., 2019).

4. Clinician Well-being

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged traditional roles and responsibilities within the healthcare system as it stretched the capacity of healthcare workers into non-traditional care roles. The all-hands-on-deck situation, for example, saw many public health staff, in Alberta, redeployed and retrained to support contact tracing and pandemic response efforts (Johnston et al., 2022). A ministerial order made by the government of Alberta in May of 2020 allowed paramedics, registered dietitians, licensed practical nurses and pharmacists, those regulated under the Health Professions Act of Alberta to work outside of their traditional scope of practice and adopt the role of what would normally be done by registered nurses (Johnston et al., 2022). Cross-training and interprofessional collaboration among regulated health professionals had both positive and negative benefits to the healthcare workforce. In Alberta, and across Canada, higher levels of healthcare worker burnout since the COVID-19 pandemic are being reported regardless of health discipline. This may be because of increased demands placed on health care workers, high stress work environments, changes in scope of practice, redeployment and increases in overtime hours (AHS Scientific Advisory Group, 2022). Burnout is causing a healthcare worker shortage, as staff from all disciplines are experiencing mental health issues, lower job satisfaction and insufficient support. This demonstrates the need to enhance evidence-based strategies to support healthcare worker’s well-being at not only the individual self-care level, organizational communication strategies, but also interventions at the systems level to build more positive work environments and supportive processes (AHS Scientific Advisory Group, 2022).

5. Health Equity

When Canadians access the healthcare system, their health outcomes are influenced by conditions which they were born in, grew up in, live in, work in or study in. The social determinants of health can be grouped into five domains: economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighbourhood and build environment, and social or community context (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion). These factors can create inequities and barriers to access, especially in vulnerable populations such as Indigenous populations, immigrants and those experiencing poverty. These inequities require a broader view of health rather than just disease state or care model (McGovern et al., 2014). The challenge for policy makers and health systems leaders is to consider how non-health related policies, such as early childhood investments, transportation, education and housing can impact the well-being and care of individuals within a healthcare system (McGovern et al., 2014). Vulnerable populations, such as Canada’s Indigenous peoples in all provinces still experience health inequities in mental health, food security and chronic illness (Kim, 2019). These inequities, which date back to colonialism, are exacerbated by continued systemic racism, low socio-economic status, poor education, barriers to accessing quality healthcare and intergenerational trauma from residential schools (Kim, 2019). The healthcare system has begun to incorporate trauma informed care, cultural sensitivity training and collaboration with Indigenous patients and communities into care at all levels. To truly address social determinants of health, in vulnerable populations, informed approaches, such as a life course approach to health development model can trace health problems back to stages of life and enable strategizing culturally appropriate interventions for better outcomes (Kim, 2019). This demonstrates the need for more collaborative stakeholder engagement in public health program planning as well as a shift in the way health promotion strategies are implemented within vulnerable populations to apply an equity lens.

A current state assessment of the healthcare system in Canada, with a focus on public health, using the quintuple aim framework provides a comprehensive and robust way to identify improvement strategies. Using knowledge of individualized concepts of health and the influence of social, economic and political forces can uncover strategies for improved patient experience. Achieving better health outcomes requires knowledge of multi-level models for optimal impact. Lowering healthcare costs is possible by understanding major contributors such as chronic disease, regional rates and modifiable risk factors. Interprofessional connectedness in the healthcare system is largely dependent on clinician well-being and strategies to support positive work environments will benefit all disciplines in the system. Health equity is an important emerging topic where the complex needs and backgrounds of vulnerable populations and determinants of health need consideration to enhance the health of the population. The solutions are not simple, but they are attainable. Public health offers an upstream approach to healthcare transformation, the most important element for success is connection.

References:

Alberta Health Services. (n.d.). Chronic Disease Prevention - Chronic Disease in Alberta. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/info/Page15343.aspx

Alberta Health Services, COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group. (2022). COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group Evidence Summary and Recommendations Managing and Preventing Healthcare Provider Burnout. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-covid-19-sag-managing-hcw-burnout-rapid-review.pdf

Barua, B., Clemens, J., & Jackson, T. (2019). Health Care Reform Options for Alberta. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/health-care-reform-options-for-alberta.pdf

Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Population and Public Health. (2021, April). Building Public Health Systems for the Future. Ottawa, ON: CIHR. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/building-public-health-systems-for-the-future-en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018). National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2018. Ottawa, ON: CIHI. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/nhex-trends-narrative-report-2018-en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (n.d.-b) Outcomes | CIHI. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.cihi.ca/en/topics/outcomes

Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) and Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion - Public Health Ontario (PHO). The burden of chronic diseases in Ontario: key estimates to support efforts in prevention. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://www.ccohealth.ca/sites/CCOHealth/files/assets/BurdenCDReport.pdf

Defo, B. K. (2014). Beyond the ‘transition’ frameworks: the cross-continuum of health, disease and mortality framework. Global Health Action, 7(1), 24804. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.24804

Fallon, C. K., & Karlawish, J. (2019). Is the WHO Definition of Health Aging Well? Frameworks for “Health” After Three Score and Ten. American Journal of Public Health, 109(8), 1104–1106. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2019.305177

Itchhaporia, D. The Evolution of the Quintuple Aim. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Nov, 78 (22) 2262–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.018

Johnston, J. C., Strain, K. L., Dribnenki, C., & Devolin, M. (2022). Meeting case investigation and contact tracing needs during COVID-19 in Alberta: the development and implementation of the Alberta Health Services Pod Partnership Model. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 113(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00604-6

Kokko, P. (2022). Improving the value of healthcare systems using the Triple Aim framework: A systematic literature review. Health Policy, 126(4), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.02.005

Kim, K., Polite, B., Hedeker, D., Liebovitz, D., Randal, F., Jayaprakash, M., Quinn, M., Lee, S. M., & Lam, H. (2020). Implementing a multilevel intervention to accelerate colorectal cancer screening and follow-up in federally qualified health centers using a stepped wedge design: a study protocol. Implementation Science, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01045-4

Kryzanowski, J., Bloomquist, C. D., Dunn-Pierce, T., Murphy, L., Clarke, S., & Neudorf, C. (2018). Quality improvement as a population health promotion opportunity to reorient the healthcare system. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 110(1), 58–61. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-018-0132-8

McGovern, L., Miller, G., & Hughes-Cromwick, P. (2014). The relative contribution of multiple determinants to health. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20140821.404487

Moir, & Barua. (2022). Comparing Performance of Universal Health Care Countries. Fraser Institute. Retrieved December 4, 2022, from https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/comparing-performance-of-universal-health-care-countries-2022.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. (November 2022). COVID-19 vaccination coverage in Canada - Canada.ca. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccination-coverage/

Report on the Auditor General of Alberta. (2014, September). Auditor General of Alberta. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://www.oag.ab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/2014_-_Report_of_the_Auditor_General_of_Alberta_-_September_2014_srwoIwD.pdf

Sutherland J, Repin N. Current Hospital Funding in Canada Policy Brief. Vancouver: UBC Centre for Health Services and Policy Research; 2014. Retrieved Nov 20, 2022, from https://healthcarefunding2.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2014/02/White-Paper-Current-Funding-2.pdf

Tzelepis, F., Sanson-Fisher, R., Zucca, A., & Fradgley, E. (2015). Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Preference and Adherence, 831. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.s81975

van Druten, V.P., Bartels, E.A., van de Mheen, D. et al. Concepts of health in different contexts: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 389 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07702-2

What Is Patient Experience? (n.d.). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. December 5, 2022, from https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/patient-experience/index.html

Wold, B., & Mittelmark, M. B. (2018). Health-promotion research over three decades: The social-ecological model and challenges in implementation of interventions. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817743893

Add comment

Comments