Early on in my career as a registered dietitian I knew that rather than counselling individuals on a diet plan for a specific disease state, I was more passionate about population health and upstream approaches to preventing illness and disease. As such, much of my career as a health promotion facilitator has been focused on applying the population health promotion (PHP) model to improve the health of youth, build capacity, decrease health status inequities, and facilitate collaborative action for preventing illness, injury and disease in the future. One health topic that has emerged over the 12 years that I have worked in school health promotion is youth mental health. Applying a multilevel approach, such as the PHP model, will identify 'who' to target, 'how' to address youth mental health and 'what' is contributing to the issue.

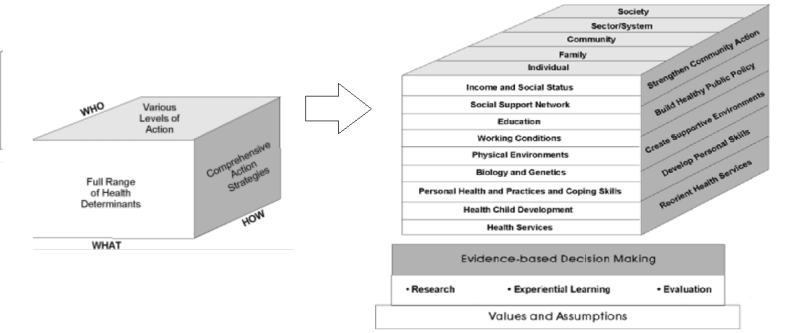

The PHP model, known widely in my professional circles as “the cube” depicts the three main components of a multilevel approach that enables a comprehensive action of a health topic (see figure 1). In addition to the three main sides of the cube, the model also identifies the need for evidence-based decision making and outlines specific values and assumptions for health promotion. For example, action on a health topic must be grounded in the understanding that the environment upholds principles of social justice and equity, and strategies must be coordinated across the levels in order to be most effective.

Beginning with the ‘who’ side of the cube, the levels of action to target for youth mental health promotion would include not only the individual, but their family, the community, the school and society. Next, the health promotion strategies on the ‘how’ side of the cube are to create supportive environments, develop personal skills, strengthen community action, reorient health services and build healthy public policy. The conditions in the environment that contribute to the health of youth or the 'what' are characterized by the social determinants of health (SDOH). The SDOH domains include economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighbourhood and build environment, and social or community context (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion).

According to Health Canada, mental health encompasses social, emotional, and psychological well-being, contributes to your overall health and is independent of mental illness (2021). In youth, mental health difficulties can have a negative effect on their relationships, educational behaviour, self-regulation as well as their morbidity and mortality (Vaillancourt et al., 2021). Since 2020, several aspects of Canadian youth’s mental health have declined, partially attributed to effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, such as social distancing, remote learning, and reduced income of their households (Statistics Canada, 2022). In Alberta, a 2021 provincial survey revealed 75% of parents and 90% of professionals indicated that their children or youth’s mental health has worsened throughout the pandemic (GOA). There is an urgent need to intervene and enhance support for youth mental health (Vaillancourt et al., 2021). Interventions and support in this life stage can have positive impacts over an individual’s lifetime in family, social, and academic domains (Vaillancourt et al, 2021). The school setting offers an ideal access point for enhancing support for this population. This is because of the relative time youth spend at school, and the additional levels of influence available such as peer relationships, supportive adults/teachers, school based mental health providers, and the overall school environment (Long et al. 2021).

If we begin to dissect the issue of youth mental health decline, using the PHP model, we may consider actions that target the youth, at an individual level. These actions can be aimed at addressing a certain aspect of their health, such as their social support network (see figure 2).

Figure 2

A Cross Section of the PHP Model Focused on Creating Supportive Environments at the Individual Level to Enhance Social Support Networks

A study by Zheng et al., (2022), examined how loneliness contributes negatively to youth mental health. There are many negative impacts, a mental health issue, loneliness has on a student’s physical health. Zheng et al. found that “compared to non-lonely adolescents, youth who report loneliness are more likely to suffer from physical health problems, with higher levels of subjective health complaints, more health-compromising behaviours (i.e., heavy smoking, excessive alcohol use, drug use), higher frequencies of doctors’ visits, and the greater chronic disease risks (i.e. respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease) in early adulthood” (2022, p. 3). Loneliness can also impact a student’s success negatively by contributing to lower academic grades and lower engagement in school (Zheng et al., 2022). The study suggested enhancing the quality of teacher support (guidance and emotional) as well as peer support (in person communication and online networking) to positively impact the environment around the youth, and in turn enhance their mental health.

Another study, suggested targeting interventions to enhance “school-belonging, student-teacher relationships, and a perceived inclusive school climate were associated with better mental health” (Long et al., 2021, p.1 ). They concluded that strategies aimed at improving peer networks in relation to bullying, victimization, and social emotional learning as well as creating a school climate where each student has at least one trusted adult could be beneficial (Long et al., 2021). While these studies identified important strategies within a school to begin enhancing support at the individual level, actions to support developing the skills of the youth’s parents and family would also add another layer of support for youth.

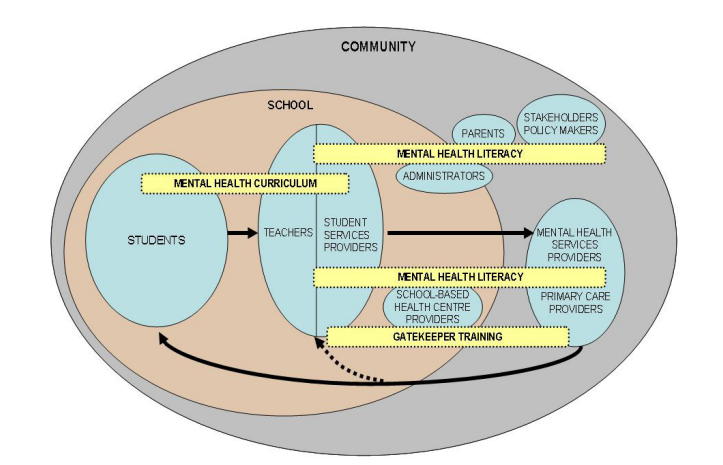

Prior to the pandemic, a Canadian school-based pathway to care model was proposed by Wei (2011). This multi-level approach identifies where youth, school staff, mental health providers, parents, community members, primary care providers and policy makers work collaboratively within multi-dimensional interventions (see figure 3). Wei outlines evidence-based interventions at the family, community and sector level of the PHP model, such as curriculum, training, and capacity building to improve mental health outcomes in secondary school students.

Figure 3

School Based Pathway to Care Model (Wei et al.,2011)

By looking beyond one level of action, and one health promotion strategy, Wei’s planned approach proposes mechanisms to address multiple determinants like healthy child development, education, physical environments, social support networks, health practices and coping skills. At an even higher level, the system that a student’s school is in, or the provincial ministry of education can also play an important role in addressing youth mental health (see figure 4).

Figure 4

A Cross Section of the PHP Model Focused on Enhancing Personal Health Practices and Coping Skills to Strengthen Community Action at the System Level

Since the Covid-19 pandemic has created new conditions for and impacts on the mental health of youth, a new strategy is required at the system level. Vaillancourt et al., suggest another layer required to address this issue is a collaboration among the federal government and provinces and territories to implement and evaluate evidence-based practice and policy” which must include “school-based mental health” (p. 630-631, 2021 ). For example, the Government of Alberta (GOA) has begun to take steps to enhance mental health support in schools. This year, they have created a grant program for school authorities to apply for called Mental Health in Schools pilot, which comes with two years of $10 Million funding for schools to apply. The GOA has outlined a list of suggested actions aimed at multiple levels to address mental health in schools (see table 1). School authorities can submit action plans, to apply for funding to support their goals for addressing youth mental health and are encouraged to use a comprehensive approach.

Table 1

Strategies from the GOA’s Mental Health in Schools Pilot Identified Within the Components of the PHP Model

The gaps are still evident, and collaboration is needed among the different levels who surround youth in Canadian schools. Policies can be strengthened at the school authority and provincial level to support the mental health of students. Health services can better coordinate services for families in their communities. Students can be empowered to have a voice in their schools to create a supportive school climate for their peers. Coordination of evidence-based actions, and continuous improvement with regular evaluation will sustain an approach and create conditions for success. Ongoing evaluation and monitoring of the health status of youth in Canada is essential to an informed plan for improvement (Valiant et al., 2021), as indicated by the PHP model. As communities, organizations, and a society, it is essential to break down the traditional siloed responses and policies, and provide mental health support for youth, their families and their schools (Reupert, 2022). It takes a village to raise healthy and happy youth with a bright future through a coordinated response and appropriate multilevel planning.

References:

Canadian Public Health Association. (2017). Canadian Public Health Association Working Paper Public Health: A conceptual framework. Retrieved October 23, 2022, from https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/policy/ph-framework/phcf_e.pdf

Government of Alberta | Children’s Services. (2021). Child and Youth Well-being Review Final Report. Alberta.ca. Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/147b587f-5d12-48e1-9366-0dfce192e794/resource/b7f863bf-43af-44ec-8897-b0dafc341665/download/cs-child-youth-well-being-review-final-report-2021-12.pdf

Government of Alberta. (2022). Mental health in schools. Alberta.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.alberta.ca/mental-health-in-schools.aspx

Long, E., Zucca, C., & Sweeting, H. (2021). School Climate, Peer Relationships, and Adolescent Mental Health: A Social Ecological Perspective. Youth & Society, 53(8), 1400–1415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20970232

Health Canada. (2021). About Mental Health. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/about-mental-health.html

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.) Social Determinants of Health - Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2001). Developing a model: Population Health Promotion: An Integrated Model of Population Health and Health Promotion. Canada.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/population-health-promotion-integrated-model-population-health-health-promotion/developing-population-health-promotion-model.html

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2022). School Health - Canada.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/programs-initiatives/school-health.html

Reupert A, Straussner SL, Weimand B and Maybery D (2022) It Takes a Village to Raise a Child: Understanding and Expanding the Concept of the “Village”. Frontiers in Public Health 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.756066

Statistics Canada. (2022). Youth mental health in the spotlight again, as pandemic drags on - Statistics Canada. Retrieved October 23, 2022, from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/907-youth-mental-health-spotlight-again-pandemic-drags

Vaillancourt, T., Szatmari, P., Georgiades, K., & Krygsman, A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of Canadian children and youth. FACETS, 6, 1628–1648. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0078

Wei, Y. (2011). Comprehensive School Mental Health: An integrated “School-Based Pathway to Care” model for Canadian secondary schools. McGill Journal of Education / Revue des sciences de l’éducation de McGill –. Érudit. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/mje/2011-v46-n2-mje1824433/1006436ar/

Youth Mental Health Canada (February, 2022) Youth Mental Health Stats in Canada. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://ymhc.ngo/resources/ymh-stats/

Zheng, Y., Panayiotou, M., Currie, D., Yang, K., Bagnall, C., Qualter, P., & Inchley, J. (2022). The Role of School Connectedness and Friend Contact in Adolescent Loneliness, and Implications for Physical Health. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01449-x

Add comment

Comments